He’s the last team member standing. At age 92, Ken Jacobson retains a steady gaze, an intact memory, a positive outlook on life, and an ability to story-tell. He’s the lone player remaining from Willamette University’s “Pearl Harbor football team,” the team that witnessed the United States’ opening play into World War II in Honolulu on December 7, 1941.

.jpg)

Image courtesy of Willamette University Archive and Special Collections

Most of Jacobson’s teammate were farm-boys, lumberjacks and ranchers, hailing from small-town Oregon--places like Molalla and Coquille. Jacobson’s father followed a railroad job to Vancouver, Washington and then joined the family floral business. Ken achieved enough success on the high school football field to catch the eye of Willamette’s coach, Roy S. Keene, whom everyone called, “Spec.” Spec ran a respected program at the small university in Salem, a short stroll from the banks of the Willamette River. The school, with a student population of about 800-900 at the time, is the oldest university in the West.

Spec offered Jacobson a scholarship to join his Willamette “Bearcat” team. “I was really a green kid in Vancouver,” Jacobson said. “There were six kids in our family and I didn’t ever think I’d get to go to college, but I was good enough of a player, and Spec got me. I’d never heard of Willamette.”

Spec took his football players under his wing, covering their tuitions and setting them up with jobs to earn room and board. Jacobson lived in a boarding house as a freshman. During his sophomore year, he and teammates Ted Ogdahl, Marshal “Mush” Barbour and Chuck Furno convinced Spec to let them bunk in a little-used training room in the basement of the gym. They brought in cots and tables, and ran a pipe across the room for hanging clothing.

.jpg)

(Photos courtesy of Ken Jacobson)

Big rally at the train station in Salem, Oregon and team members model their travel attire

Besides knowing how to nurture football talent, Spec held another advantage: an upcoming bowl game in the Territory of Hawaii. Jacobson remembered, “When they said we were going to Hawaii--I’d never even really been out of Vancouver.” As a young boy, Jacobson had seen the ocean at Long Beach, Washington...maybe twice.

Spec recruited most of the ball players with the carrot of the Hawaii trip. “Of course, I’d have gone there no matter what,” Jacobson said. The trip lured players away from bigger schools, like Marv Goodman, who had planned on attending the University of Oregon.

Spec spent years preparing to take his team to this round-robin football tournament in Honolulu, called the Shrine Bowl. Sponsored by the Shriners, the game guaranteed a $5,500 payout--enough to cover travel expenses, plus a small profit for the athletic department. Teams in the three-game series included San Jose State College, the University of Hawaii, and Willamette. The kick-off date was December 6, 1941.

The week before their Hawaii trip, Willamette played cautiously against Whitman, as nobody wanted to risk an injury and miss the big journey. Despite their tentative play, they beat Whitman 28-0. Willamette, the Northwest Conference champion, had an 8-2 record, including six shut-outs. They’d outscored opponents 218-7.

Oregon State Senator Douglas McKay, a close friend of the Willamette coaches, accompanied the team to Hawaii, along with 21 other civil and school leaders from Salem. Senator McKay brought along his 18-year-daughter, Shirley, a Willamette freshman. Shirley’s new boyfriend from school, Wayne Hadley, booked a ticket for himself. Others on the trip included Willamette’s cheerleaders, Manager Dick Kern, Publicist Gil Lieser, and Mrs. “Spec” Keene.

Tensions in the Pacific and fear of Japanese attack had created doubt that the trip would unfold. Most intelligence, however, suggested an attack at Malaya or the Philippines, not Hawaii. Still, nobody knew for sure that the journey would happen until they actually set sail.

On November 26, hundreds of supporters gathered at a noisy rally at Salem’s Southern Pacific railroad depot to see the Willamette delegation off. At 10:30 AM, the train rolled south toward the Port of San Francisco. On November 27, the Willamette and San Jose State teams and their boosters boarded the SS Lurline luxury passenger liner--one of few ships still braving a twice-monthly voyage across the Pacific. The travelers envisioned the exotic island paradise awaiting them ahead.

Ken Jacobson and Mrs "Spec" Keene share a seasick moment on deck lounge chairs

Brimming with excitement, the Willamette party glided under the four-year-old Golden Gate Bridge. The Lurline cruised along the coastline, then stopped for the day in Los Angeles to pick up more passengers. On November 28, they took to the open seas.

Three days earlier, and over 5,000 miles away, a Japanese convoy led by six aircraft carriers had already left Japan. They were also on their way to Hawaii, but for entirely different reasons.

The Willamette boys bunked two to three per cabin on the Lurline, with a wash basin in the room and a full restroom down the hall. They didn’t have much trouble sharing the sink because, as Jacobson recalled, “I didn’t shave then. None of the guys were old enough to shave.”

Rocky waves nauseated Willamette’s football players, many of whom had never seen the ocean. Several had difficulty keeping food down, dropping several pounds of weight during the voyage. Jacobson said, “At first, they ordered these big breakfasts, and we started eating, and then all of a sudden they got sick. I was eating breakfast, and then all of a sudden, I hit the rail, and never ate another meal.”

On November 30, two days after the ship left Los Angeles, Lurline’s first assistant radio officer, Leslie E. Grogan, intercepted some unusual low-frequency radio signals. The transmissions originated from a station in Japan, with replies moving south-easterly toward Hawaii. This continued the next two evenings. Upon reaching Honolulu on December 3, Grogan relayed the information to Lt. Cmdr. George Warren Pease, the military intelligence officer of the 14th Naval District. There is no record that the information ever got forwarded up the chain of command.

Onboard, Willamette’s football players dressed in their white v-neck travel sweaters for their Hawaiian arrival. Their hosts, the Aloha chapter of the Shriners, met and greeted the teams. They furnished the players with cone-shaped straw hats which mimicked the conical ones the Shriners wore. University of Hawaii coeds supplied flowered leis, while Hawaiian tunes played and hula girls swayed.

Both the Willamette and San Jose contingents checked into the opulent Moana hotel in Honolulu, one of only two hotels on Waikiki Beach at the time. Their nine-day stay in a double room on the “American plan” cost $54 per person. The Moana stands twelve miles east of Pearl Harbor.

Coach Spec gathered his team on the practice field that afternoon for conditioning and reviewing of game plans. The players had sea legs and could barely walk straight. The transition from Salem’s 30 degree temperatures to 85 degrees in Honolulu also took a toll. Jacobson said, “I remember going to the football field, just to see it. We put on gear. We weren’t gonna practice, just to loosen up. But I remember running out there and falling down. We didn’t have much time to recover.”

Three days later, the Willamette Bearcats played what was slated as the first in the three-game series. Their opponent was San Jose State, with profits from this opening Shriner’s game designated for disabled children. The game started at 2:30 PM on Saturday, December 6.

Willamette’s players donned their leather helmets and stepped onto the field of Honolulu Stadium. Back home, bleachers at Willamette’s Sweetland Field held about 900 fans. Honolulu Stadium held 25,000. The young Bearcats looked in awe at the crowds in the stands; they had never seen such numbers before.

A full 24,000 had shown up to watch the Shriner’s game, many of them in military uniform. Undoubtedly, a number of the fans included servicemen enjoying an afternoon leave from their Naval ships docked in Pearl Harbor.

Since the 1920s, Shriner football games had been the biggest and most popular sporting event in Hawaii. Spectators for this Willamette-San Jose game comprised a tenth of Honolulu’s current population. This recorded the largest crowd in the stadium’s history.

With just 27 members on the roster, Willamette’s athletes played both offense and defense, generally substituting only due to injury. Jacobson played running back and linebacker. The Bearcats performed well for three quarters, but fell behind in the fourth, losing with a final score of 20-6. The players didn’t care to make excuses, but likely their stormy sea ride played a role in sapping their stamina. Jacobson said, “We gave them a pretty good game, though.”

That evening, most of the team went out on the town, but Jacobson stayed at the hotel. “I was so darned beat up; I didn’t go out.” Most anticipated some tropical rest and relaxation, and looked forward to the next two games of the Shrine series: San Jose vs. Hawaii on December 13 and San Jose vs. Willamette on December 16.

.jpg)

Coach "Spec" Keene and Ken Jacobson

The next morning, a bright December 7th, Willamette’s players and boosters gathered for Sunday breakfast at the Moana Hotel. Some had just returned from early church services. A few finished eating and wandered onto Waikiki Beach. The Shriners had scheduled a sightseeing excursion for them, including a picnic on the other side of the island with some University of Hawaii co-eds, a stop at at the Shriner’s children’s hospital, and a tour of the base at Pearl Harbor. The bus and tour guide never arrived.

Jacobson described:

I knew they had planned this picnic for us, or gathering, with the University of Hawaii, and they were supposed to come by at 9:30 in the morning. And so, we’d had breakfast, and we were out, enjoying the sunshine, looking, you know, and waiting for that bus to come, and the bus didn’t come. While we were sitting out there, we saw planes fly over. They were just silver specks up in the sky. And then somebody got up and walked through the hotel and went out on the beach and they said, ‘Hey, there’s maneuvers going on out here.’

So we walked to the beach and we could look out over the ocean and we saw these airplanes up there, puffs of smoke around them. ‘Yeah, look how real, how close those planes are!’ Every once in a while, we could see water shooting up, but they were so far out. When they dropped bombs, you could see the water shoot up real high.

Those still inside the Moana watched through breakfast room windows at the water spurts on the ocean, one splash just a hundred yards away. A Moana waiter assured his guests that these were merely whales spouting. In comedic fashion, they all marched outside for a better look. But after a half-dozen of these supposed whale spouts, they realized something else was afloat. In actuality, the US military was shooting up 3-inch anti-aircraft missiles, and the spent rounds dropped down, exploding in commercial and residential zones of Honolulu.

From the front of the Moana, players saw several formations of planes flying low and directly overhead. Sirens sounded. They still assumed these were maneuvers by the army and navy corps, though they seemed awfully close off-shore. “The Japs must be after us!” one woman from the group unknowingly joked. Soon the sky filled with black, oily smoke, mostly coming from the direction of Pearl Harbor.

Japanese Zero on bombing run, December 7th (Courtesy Library of Congress)

Jacobson said:

The planes that we saw flying over were the second flight that came in. The first flight [at 7:55 AM] were the ones that had gone in and did all the damage on Pearl Harbor. And we didn’t even see those. You couldn’t see Pearl Harbor up from where we were. We could get on the top of the hotel and look out there and see the smoke out there.

Shirley McKay and Wayne Hadley had gone down to the beach. She told Tom Wilson in his “When Willamette Went to War” piece (December 7, 2003):

http://www.d3football.com/notables/2003/when-willamette-went-to-war:

“We had boxed lunches packed for the tour, and some of us were swimming while waiting for the bus. Then a soldier came along and told us to walk under the trees and go back to the hotel because the island was under attack.”

In Jim Campbell’s story “Who Could Forget”

http://library.la84.org/SportsLibrary/CFHSN/CFHSNv12/CFHSNv12n1c.pdf,

Wayne Hadley is quoted: “We could see splashes and air bursts, but like so many others, we thought they were part of Navy maneuvers. We didn’t realize we were seeing the start of World War II for the U.S.; mostly we just heard noise.”

Tackle James Fitzgerald spotted a red ball under the wing of a plane. He understood that all the smoke and noise coming from the direction of Pearl Harbor was no simple maneuver.

View from roof of Moana Hotel, December, 7th

In “Who Could Forget” by Jim Campbell, Willamette center Pat White is quoted:

Mush (Marshall Barbour’s nickname) and I went to the beach to string barbed wire,” he explained. We dug some trenches, too. By then, there were machine gun emplacements and we protected them. You have to understand that the threat of a land invasion was still very real to us.

Spec corralled his team and boosters into the lobby and instructed them to stay put. Around 1 PM someone turned on a radio. The announcer said, “Be calm, but the island of Oahu is under enemy attack, and the sign of the rising sun has been seen on the wings of the plane.”

Spec ordered a team meeting. Most of Willamette’s team members wanted to formally enlist in the military on the spot, but Spec told them no. He said he was their acting guardian since he’d brought them out of the States. Spec told them that while they couldn’t enlist, they could volunteer.

The police declared a state of emergency beginning that evening, enacting martial law and ordering everyone off the streets. Rumors circulated that the Japanese had sabotaged the drinking water by contaminating the water towers and storage tanks.

Jacobson said, “That night was really scary. It was completely blacked out, and they had all kinds of rumors going around that the Japs were gonna land.” The team and boosters all stayed at the Moana that night. The next morning, military police dropped off a pile of antiquated WWI rifles in the hotel lobby.

Quarterback and fullback Earl Hampton is quoted in “When Willamette Went to War” by Tom Wilson:

Then Coach Spec and some military personnel came by and they had rifles with bayonets stacked in the lobby of the hotel. They told us that they were expecting the Japanese to attack the island and that Waikiki would be a likely place. They were digging trenches out by the beach, while some of us helped them.

Senator McKay demonstrated use of the bolt-action Springfield M1903 rifles. McKay, a WWI veteran who’d been wounded at war, gave the men a pep talk. They were each issued a rifle, along with a small amount of ammunition, and taught how to inspect, clean, load, and aim it. They even learned how to use the Bayonet. Officials told the young men that they had to be prepared to defend the beach and island from the Japanese.

Most of the players had never actually seen a gun before.

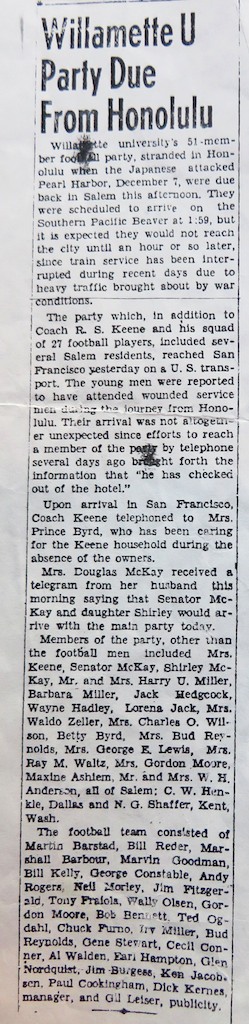

The military closed and censored regular channels of communication, but on Monday, December 8, Spec got word to Oregon Governor Charles Sprague that the team was safe. Spec used a network of amateur radio operators to send his message in the form of a radiogram. On December 10, Senator McKay relayed further information to the sports editor at a Salem newspaper. Reports quickly disseminated to anxious friends and family back home, whose first thoughts of the Pearl Harbor attack had been for the security of their loved ones in Honolulu. Most players worried more how their families were taking the news than for themselves. Some players also found ways to contact relieved family members directly, but Jacobson’s family didn’t even own a phone in 1941.

Douglas McKay (Courtesy library of Congress)

Spec volunteered the men in his entourage, players and boosters alike, to assist the Army, essentially temporarily conscripting them. Their first task was guarding the perimeter of an ammunitions stash. The US Army Corp of Engineers had been bombed from their headquarters the previous day, and moved their ammunition storage to the fenced Punahou High School in the hills above Honolulu. The military instructed the players to call out, “Halt, who goes there! Stand and be recognized!”

Pinahou High School, 1941 (Coutesy Library of Congress)

They went on sentry rotation, singing or talking loudly as they approached each other, so they’d know who it was. Willamette’s players covered one shift, San Jose players a second, and the National Guard a third. They slept on box-spring mattresses on concrete floors in the school’s typing room and science building. Jacobson said, “We were so darn tired; we didn’t get any sleep. We were on three hours, and off six.”

Nights were especially nerve-wracking for the players, the pitch-dark crowded with mosquitos and suspicious noises. Evening winds scattered garbage around and knocked coconuts from trees. Officials ordered Hawaii on black-out, with no traffic or lights anywhere; guards were instructed to shoot out any visible lights after 5 PM. Even cigarettes were forbidden, in case the Japanese might detect their glow.

Understandably, the men felt little confidence in their abilities with the rifles. Fortunately, none of them ever had to fire their gun. Later they called it miraculous that nobody accidentally shot each other.

Jacobson recalled:

The national guard was in charge of us. One of the national guard had a riot gun, and they had an office in there [at Punahou], and this guy had a sawed-off shotgun. He came in with the shotgun and put it down on the table and it went off. I was in that room when that guy came in and did that, and it went off through the ceiling, and the room up above was where we all slept. I went upstairs to see if anyone was up there. And that scared us, but it didn’t hit anyone. It went through the floor.

On his second night of patrol, freshman running back Glenn Nordquist used the opportunity of guard patrol in the darkness to have a quiet conversation with God. He promised that when he was able, he would return to the pursuit of full-time ministry.

The Willamette men had little idea how long they’d continue at their guard jobs. Some in the group assumed they might be stranded in Honolulu until spring. Jacobson said, “We didn’t know anything out there. We were just stuck out there. After we’d been out there three or four days, I think we got into a routine, and kinda got used to it, and they got it figured out that the Japs weren’t coming in there.” Players continued their guard duties for ten days. Ultimately, they received fifty dollars for their military service--a rate of five dollars per day.

Women from the Willamette group volunteered as nurses’ aids at Tripler Army Hospital. They helped overworked staff with a group of children hit by shrapnel on their way to Sunday School the morning of December 7. The women kept the children company until their families could locate them, assisting with meals and reading to them. The women also made beds, helped change dressings, carried food trays, and bathed and took temperatures of the wounded.

In the meantime, Spec and Senator McKay worked behind the scenes on behalf of both the Willamette and San Jose parties. Their immediate concern? Finding a way back to Oregon.

Honolulu police clued Spec and Senator McKay to two approaching hospital ships. They negotiated an arrangement with the captain of the ocean liner SS President Coolidge to secure passage from Honolulu to San Francisco for the Willamette and San Jose groups. They would join the Coolidge in exchange for assistance with the gravely wounded passengers on the ship.

On December 7, the day of the Pearl Harbor attack, the SS Coolidge had been traveling to San Francisco when it was diverted to Honolulu to pick up injured soldiers. The Coolidge, a former luxury cruise liner, arrived in Honolulu on December 17 with evacuees from the Philippines. Officials quickly assembled a small on-board hospital to transport soldiers wounded at Pearl Harbor to California medical centers. Two Navy doctors and three Navy nurses would care for 125 patients.

On December 19, the Coolidge was ready to leave Honolulu. The football groups received only two hours’ notice. Jacobson said, “The day that we got to come home, they had scheduled a trip to Pearl Harbor so we could see the damage that was done, and they were gonna take us out there for a sight-seeing, and then instead they said we were going home.”

Ken Jacobson on deck

Willamette’s players had to sign a form promising to assist with evacuation of wounded soldiers from the ship, if necessary. Two players were assigned to one patient deep in the bowels of the ship. The players acted as orderlies, carrying patients to the operating room, feeding them, and changing dressings. They also chatted with patients to boost morale.

Jacobson explained:

They said that they’d let the football team go if we would agree to get the wounded people off first, and kind of look after them if we got torpedoed. I remember going by the rooms and you could look through the windows at them, and see them in bed there, and they were all burned.

Scores of soldiers had suffered amputations or burns. The smell of burnt flesh overpowered the young men; Fitzgerald vomited over the ship’s rail.

Convoy escort plane

Jacobson said, “The first day we were on, I helped carry a kid. They were gonna cut his leg off. We formed an arm lift and carried him into the room where they cut his leg off. I didn’t go down in there because the smell was so bad. Burned flesh is the awful-est.”

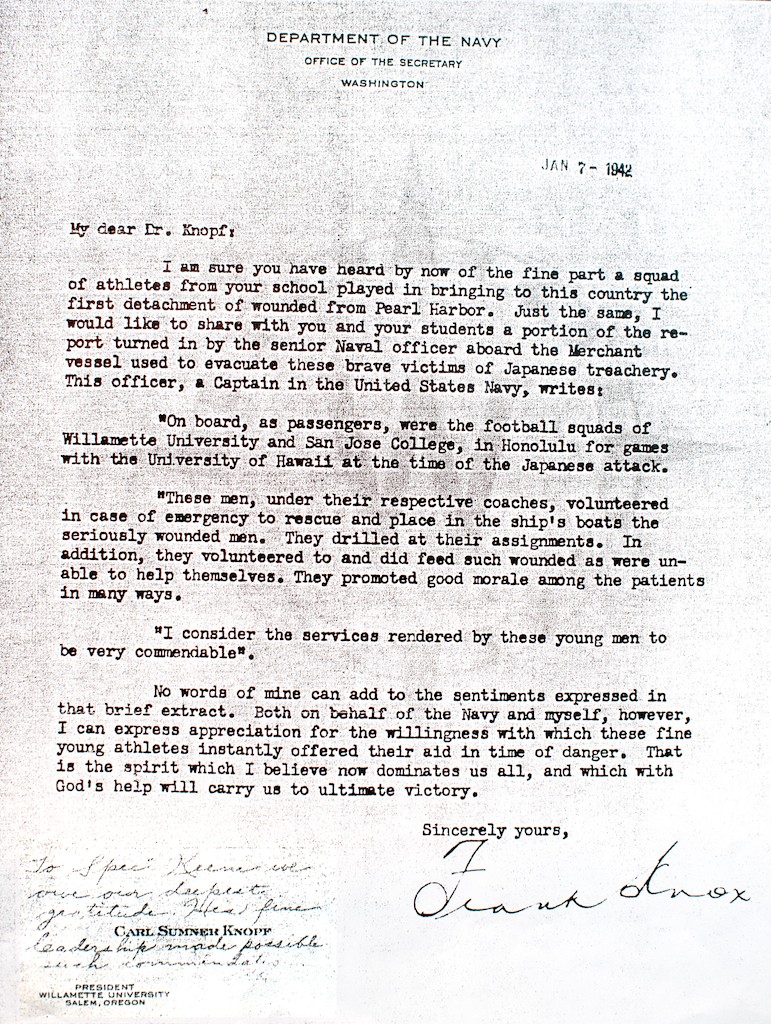

Frank Knox, the Secretary of the Navy, later wrote the following to Carl Knopf, president of Willamette:

On board, as passengers, were the football squads of Willamette University and San Jose College, in Honolulu for games with the University of Hawaii at the time of the Japanese attack.

These men, under their respective coaches, volunteered in case of emergency to rescue and place in the ship’s boats the seriously wounded men. They drilled at their assignments. In addition, they volunteered and did feed such wounded as were unable to help themselves. They promoted good morale among the patients in many ways. I consider the services rendered by these young men to be very commendable.

The women from Willamette’s contingent slept in crammed third class cabins. They rolled bandages, washed dishes and generally assisted the overtaxed nursing staff.

The only bunk space available for the team lay below the water line. Since they feared that a Japanese submarine torpedo hit could entomb them, many wisely opted to sleep on deck level instead.

Jacobson said:

Where we slept was steerage, way down, and I don’t ever remember going on my bunk way down. We had a bunk, where we put our suitcases. I think I did my sleeping up in the lounge. I know that not any of us really went down in the room where we were supposed to sleep.

Designed for 800 passengers, the Coolidge carried 1,200, and sailed seven days instead of the normal four. Jacobson said, “We got to eat in the main [second class] dining room there. I know that the last couple nights we had steak every night because they were running out of [standard] food.”

The military cruiser Detroit and destroyers Reid and Cummings escorted the Coolidge in a convoy which included a transport ship and the USS High L. Scott. Halfway through the trip, the destroyer escorts switched with units from San Francisco. They had to take a circuitous, zig-zag route, changing directions every fifteen minutes. Jacobson said, “Of course, they were sinking ships like mad. Every morning, you could see the cruiser out there, you’d see that sea plane take off, fly and come back.”

The ship travelled with all exterior lights extinguished, and nobody was allowed to walk along the deck after dark. Passengers kept life jackets with them 24 hours a day, wearing them constantly the final three days. They could throw nothing overboard, even used patient bandages, for fear of leaving a trail for the Japanese.

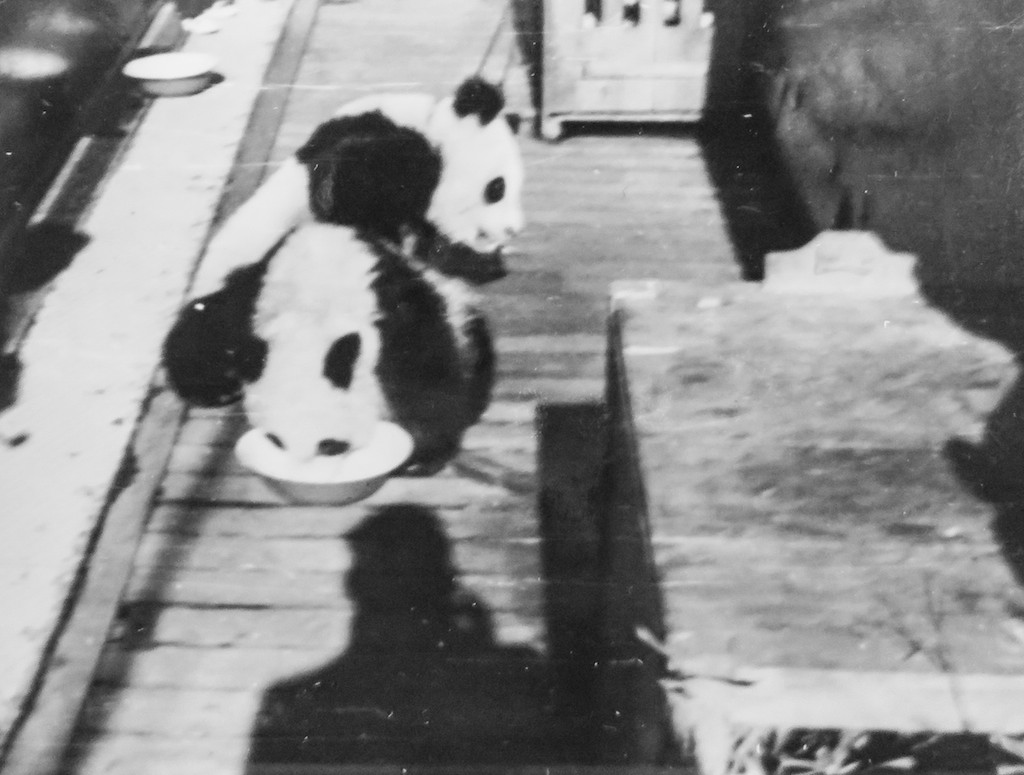

Because Willamette’s football players had been so helpful, the captain granted them full access to the ship. The players encountered some surprising passengers on the first class deck: two pandas from China. Madam Chiang Kai-shek had gifted Pan-dee and Pan-dah to the U.S. as part of her “Panda Diplomacy” program. Between 1936-1941, Madame Chiang sent pandas to the United States to help secure friendship with pre-communist China. She hoped to gain support American support for China following its own recent Japanese invasion.

Pan-dee and Pan-dah had flown over Japanese-occupied China on their way to the Philippines, where the animals boarded the SS Coolidge. At port in Manilla, the captain ordered the ship camouflaged. The crew used brushes on long poles to paint the white ship gray. They locked the port holes and colored the windows black. The captain even threatened to camouflage the distinctive black and white pandas. One of the animals accomplished this somewhat on his own when he got into the camouflage paint while playing on deck.

Pan-dee and Pan-dah on deck

Jacobson said, “We had the run of the whole ship. That’s how we were able to get the pictures of the pandas. They were young pandas. We could walk by them. They had cages for them, but they would take them out.”

As the ship approached San Francisco, anxieties peaked. Passengers had to stay dressed in daytime clothing.

Jacobson said:

You could listen to the radio in the lounge. You could pick up the San Francisco radio stations, and you could hear of all the ships that were being sunk. The closer we got, the more the shipping lanes narrowed. Of course, we took a round-about way to get in. I don’t think we were in the regular shipping lanes. But I know the last night, nobody slept. We all stayed up on the deck.

At 7 AM on December 25, 28 days after they’d originally left San Francisco, the Coolidge sailed under the Golden Gate Bridge. To most, it felt like a miracle from God. The Willamette group burst into tearful song, California, Here I Come! A number of Willamette family members and friends met the ship at 8 AM. Other Oregon families received joyful phone calls from San Francisco. Jacobson grinned, “Oh, boy, that was Christmas Day! That was a good Christmas Day!”

As it turned out, they’d arrived just one day later than their originally-scheduled return.

Nobody remembers much about the remainder of the journey home. Exhausted, they got on a bus, then a north-bound train. With school out for Christmas vacation, few awaited them in Salem.

Plus, there was a war on.

Military officials asked Senator McKay not to disclose specific details of the destruction and operations he’d witnessed in Honolulu, lest the information assist the Japanese. In fact, much of the Willamette story didn’t catch the public’s attention until about 15 years later.

Nearly all of Willamette’s football players eventually joined the military. Only one player, Bill Reader, died in action. Ted Ogdahl, a Marine, was seriously injured while attempting to take a beach in Okinawa. Ogdahl collapsed on the sand and played dead. This wasn’t difficult since he was already nearly gone, but he survived.

Ship laying anti-sub nets, San Francisco Harbor

Out of the 27 football players, 25 returned to Willamette to complete their educations. Several even re-joined the football team.

Roy S. “Spec” Keene continued his 17-year career at Willamette, coaching football, basketball and baseball. The school considers him the “father of Willamette athletics.” In 1947, Spec accepted the position of athletic director at Oregon State University, where he worked another 26 years.

Senator Douglas McKay became Oregon’s governor and later Secretary of the Interior in the Eisenhower administration. In his honor, Douglas McKay High School opened in Salem in 1979.

Shirley McKay and Wayne Hadley commenced a 60-year marriage and rich family life in November 1942. They’d had their first date at a Willamette football game and remained avid supporters of Bearcat athletics throughout their days. Family lore claimed that Wayne travelled with the team to Hawaii because he didn’t trust all those football players around his beloved Shirley.

Glenn Nordquist honored his Hawaii guard-duty promise to God and became a Baptist pastor. In 1951, he spoke at a Pearl Harbor service in Portland, where he met Japanese Captain Mitsuo Fuchida. Fuchida, also a speaker at the service, had been lead pilot in the Pearl Harbor raid. Fuchida converted to Christianity soon after the war and became a minister. The two pastors had a heart-to-heart talk about their spiritual beliefs and memories of Pearl Harbor Day.

James Fitzgerald joined the Marines, flew bombing missions in the Pacific theater, married Karin, had four children, and served almost 50 years as a state and federal judge in Alaska.

Earl Hampton served in the Navy, married Connie, had four children, and earned his PhD. He worked as a teacher, principal and superintendent at various school districts throughout Oregon. Most of the remaining team members became football coaches, teachers, business people, and lawyers.

The SS Coolidge functioned as a troopship only a year, hitting a submerged mine and sinking in 1942. The military acquired the SS Lurline, painted it gray, and used it to transport troops throughout the war. In the 1960s and ‘70s, the Lurline operated as a cruise ship until getting scrapped in 1987.

Pan-dee and Pan-dah eventually reached their destination of the Bronx Zoo.

Ken Jacobson returned to Willamette as part of an Air Corp officer training program. He said, “Velda and I got married in ’42, when it was apparent that--we didn’t know how long we were gonna make it. And so we got married. We were not going to get married until I finished school, but we decided we’d better get married.”

Spec found Velda a job in Salem. During the war, Ken Jacobson was stationed at 11 different bases in three years’ service. At his last assignment, he worked as a radio operator in Brazil. After the war, Jacobson went back to Willamette to finish his final year.

In 1947, Dallas HIgh School--20 miles west of Salem--needed an assistant football coach. Jacobson qualified for the PE and 9th grade math teaching positions. In addition, the principal convinced Jacobson to fill the following coaching slots: JV basketball, head wrestling, head track and head tennis. Jacobson wondered how he could coach basketball and wrestling at same time. He knew nothing about wrestling, “But the kids did, and the next year we got the janitor to help out.”

Jacobson earned $2,760 his first year, $360 of that for coaching. Dallas High School didn’t have a track. “I found one hurdle and they had a shot,” he said. They didn’t have a football field, either, so Jacobson designed and built his own. He made do with the tools available.

Members of the 1941 Willamette football team gathered regularly over the years. In 1991, Wayne and Shirley McKay Hadley organized a trip to Honolulu to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Pearl Harbor attack. Fifteen of the 16 or 17 living players made the journey. Jacobson hadn’t been back since 1941.

The football veterans and their wives visited, reminisced and stopped by Punahou High School. In 1941, the military had seized their sightseeing bus for emergency transportation, so the team missed their excursion. In 1991, the bus arrived on schedule, and the men finally got their Pearl Harbor tour. “We had a really good time,” Jacobson said.

Willamette inducted the entire “Pearl Harbor football team,” as they are now called, into their Athletic Hall of Fame on September 13, 1997. Along with the team, they inducted Wayne and Shirley McKay Hadley for their service and support of Willamette athletics.

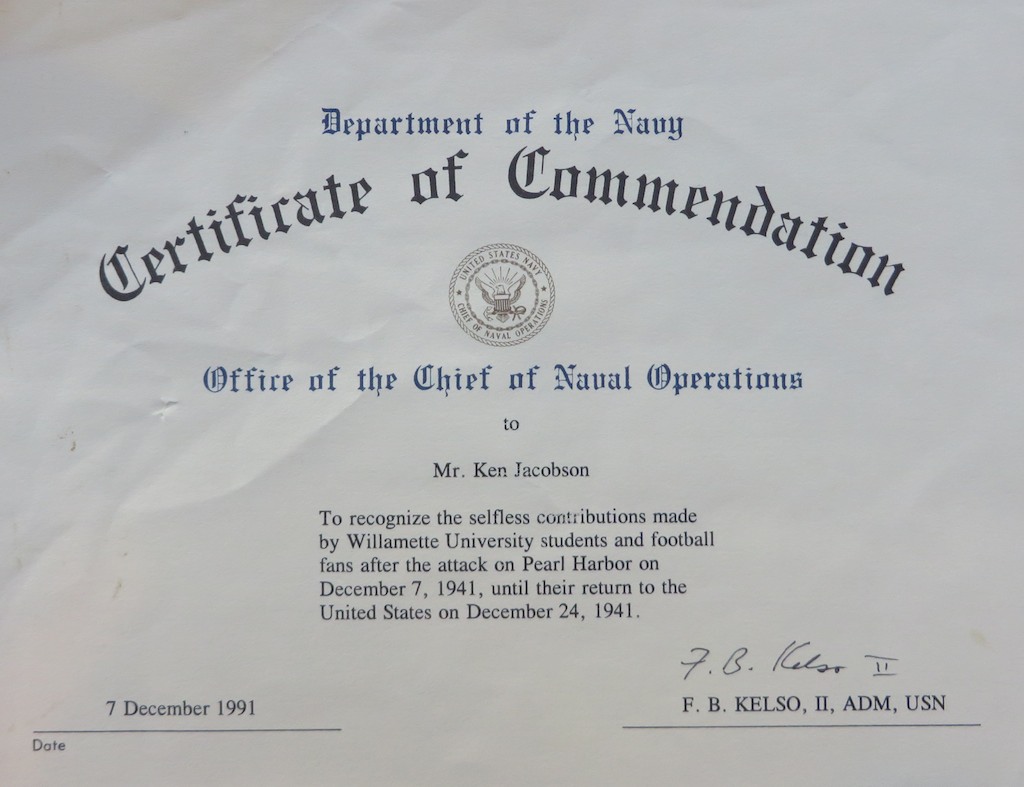

Commendation awarded to all Willamette Pearl Harbor team members

Over the years, Ken and Velda Jacobson returned to Hawaii a couple more times, and enjoyed nine uneventful, peaceful cruises together. He’s proud of how they put their three kids through college without borrowing any money. Ken and Velda were married 67 years. “She passed away in 2010; we had a good marriage.”

On October 13, 2013, the Honor Flight program flew Jacobson to Washington, D.C. to see the WWII monument. Asked for his overall impression of the war, he responded, “I’m lucky to be here!”

And our nation was fortunate to have men like Ken Jacobson in place in Honolulu, young men of determined character who performed faithfully with the limited resources at hand, never hesitating despite not knowing what would happen day by day.

Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox concluded as much in his January 7, 1941 letter commending the Willamette team:

Both on behalf of the Navy and myself, however, I can express appreciation for the willingness with which these fine young athletes instantly offered their aid in time of danger. That is the spirit which I believe now dominates us all, and which with God’s help will carry us to ultimate victory.

Ken Jacobson, Dallas, Oregon, February 2014

.jpg)

Willamette cheerleaders and players ................... Buddy Reynolds and Ken Jacobson

Cheerleaders and team preparing to leave Salem.... Ken Jacobson

Sight-seeing in Los Angeles before boarding SS Lurline .... Arriving in Honolulu

.jpg)

Image coutesy of Willamette University Archives and Special Collections

Jean and Ken, February 2014

.jpg)

(front row, from left)

Irv Miller, Cecil Conner, Pat White, Tony Fraiola, Al Walden, Jim Fitzgerald, Buddy Reynolds, Chuck Furno

(second row from left)

Earl Hampton, Bill Reder, Martin Barstad, Ted Ogdahl, Jim Burgess, Gene Stewart, Glenn Nordquist, Wally Olson

(third row from left)

Dick Kern (manager), Paul Cookingham, George Constable, David Kelly, Ken Jacobson, Allan Barrett, Marshall Barbour, Clarence Williams, Assistant Coach Howard Maple

(back row from left)

David Kurtz, Robert Bennett, Gordon Moore, Andrew Rogers, Neil Morley, Marv Goodman, Carrel "Truck" Deiner, Coach Roy S. "Spec" Keene

Note: David Kurtz, Clarence Walden and Coach Maple did not make the trip to Hawaii.